You might not have heard of Nicolas Winding Refn but I can assure you that you have heard of his movies. Refn is a Danish director who has made films in his native country and within the Hollywood system. His films feature some of the most stylised violence seen in the cinema since the Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction or the Kill Bill series. Refn has admitted that he is a fetish filmmaker and he believes that cinema is a very voyeuristic medium. I will analyse how Refn constructs his spectacles of voyeurism and violent fetishism and consequently what he is suggesting about classic American genre films and the nature of the modern hero within those films. I will look at Bronson (2008), Valhalla Rising (2009), and Drive (2011). This post has been adapted, modified, elongated, and otherwise improved from a presentation I gave on March 8 2013 in University College Cork entitled “Drive: The Urban Western, From Cowboys to Stunt Men”.

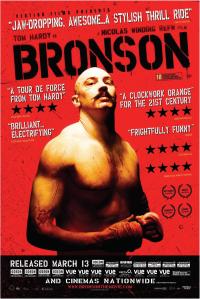

Bronson is a film about the notorious English prisoner Michael Peterson who has been labelled as one of the most violent and expensive prisoners ever. The film is usually held in high regard due to Tom Hardy’s excellent portrayal of the title character but the the spectacle of the violence created in Refn’s film is something to behold. Hardy’s character is a seemingly despicable person but is presented to us as a kind of sympathetic individual even while he commits various acts of brutality. However, there appears to be a certain code and ethic by which the character lives by. There are glimpses of the strict fitness regime he keeps and how the structure Bronson lives by is the thing that keeps him alive. The viewer is allowed glimpse into the enclosed space of the prison to see a character who would evoke a sympathetic response due to our affinity for a protagonist who sticks to a code. Bronson lives by a coded madness where he guarantees the audience destruction and violence. In the scenes where Hardy talks in front of a crowd we see Refn’s commentary on the viewer’s voyeuristic love for violent blood baths. Bronson also introduced Refn’s ability to craft the perfect soundtrack to accompany his fetishistic visuals. Digital Versicolor by Glass Candy runs through the film which would be seen replicated to a greater extent in Refn’s latest film Drive.

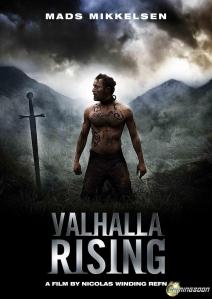

The next project which Refn conducted was a drastic departure; a film set in 1000 AD, Valhalla Rising stars Mads Mikkelsen as the unflinching mute warrior who is simply referred to as One Eye and who is being held captive by a Norse chieftain. The film is so sparse with speech that there is only around 120 lines of dialog in the entire film. The voice of this film is again in the spectacle of the visuals that Refn constructs. Mikkelson, a good friend of Refn’s, is at one stage tied with a rope to a large wooden pole sticking into the muddy mores of the barren landscape. Mikkelson’s One Eye is then forced to fight two men for his life. As his finisher move, One Eye ties a mid-section of the rope that is attached to him firmly around the neck of one of his attackers and simply runs hell for leather away from the pole causing his neck to snap. In my list of favourite Refn killing scenes, this one even tops Drive‘s head smashing elevator sequence. One Eye is another hero with a kind of sick code given to him by Refn. He is a mute and so does not speak for the entirety of the film. This adds to the visual spectacle of the violence that One Eye engages in. At first glance the poster seemingly offers a kind of medieval beat-em’-up romp but the film is in fact a more existential question of the nature of man as much of the film takes place on board a boat in the middle of nowhere bound for a similar destination. Valhalla Rising is another of Refn’s films which is heavily influenced by Keenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1964). Refn takes Anger’s imagery to the medieval period by creating sadistic and sexual scenes melded into one. Like Bronson, One Eye is topless for a lot of the film and the violence he partakes in is highly sexualised. Interestingly, Refn originally wanted Scottish instrumental outfit Mogwai to score the film which would have marked another high-point in Refn’s fantastic soundtracks. Sadly, this was not to be but if Mogwai’s soundtrack to Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait is anything to go by, it would have been fantastic.

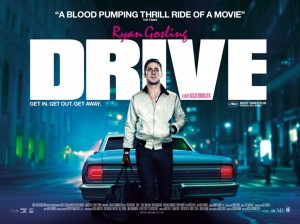

“You give me a time and a place, I give you a five minute window. Anything happens in that five minutes and I’m yours. No matter what. Anything happens a minute either side of that and you’re on your own. . . I don’t carry a gun.” This is the code of morales and strict work ethic by which Ryan Gosling’s character of the Driver follows in Drive. Refn’s 2011 film Drive is arguably his masterpiece. Starring Ryan Gosling as the Driver (with no name), Albert Brooks as the villain, and Bryan Cranston as the laughable mentor, Refn constructs a challenging film that plays with the concepts of traditional American cinematic genres. Gosling as the Driver spends his days as a Hollywood stunt man and his nights behind the wheel of getaway cars for members of the Los Angeles criminal underworld. There are only 3 car chase scenes in the film despite what the poster or title would suggest and these are very short. These chases echo the Western genre where cowboys are rarely on top of their horses for extended periods of time, despite the fact that their mode of transport essentially defines them. Refn is a European director making a genre film with an American star. This grouping points to Italian directors Sergio Leone’s Western films that he made with Clint Eastwood as the gunslinger/cowboy who arrives out of nowhere and as Jennifer McMahon would describe “outwardly and inwardly manifests the notion of loneliness” (13). Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). In this film all three characters are convening on a location where money lies with the intention of taking it all for themselves. In the film the Ugly (Eli Wallach) and the Good (Eastwood) team up at one stage but this relationship ultimately ends on unfavourable terms, there is a parallel relationship in Drive between the characters of Bryan Cranston and Ryan Gosling. Cranston’s character Shannon merely utilises Gosling’s driving skills as a way into a deep criminal underworld. He is a chancer and a character who functions without a code and this ultimately spells his downfall. While Gosling’s character can also be read to have suffered due to his code, he only does so by encountering another character who utilises a strict code, the character of Albert Brooks. He is the Lee Van Cleef of the film, the Bad in terms of Leone’s film. Brooks’ crime lord character is an unrelenting figure who has a fetish for knives and promises death to any characters who either fail or contradict him. By presenting a character tree similar to Leone’s Westerns, Refn gives the audience a representation of their fascination for a coded hero, much like the modern viewer’s affinity for both Batman’s no kill policy and the Joker’s commitment to unpredictability.

Another classic Western which can be seen as an influence on Refn’s Drive is George Stevens’ 1953 film Shane starring Alan Ladd as the title character. Ladd’s holy cowboy character is a heavenly presence dressed in white fatigues who descends from a high mountain to help an innocent family from marauding bandits. In the key scene where Shane arrives to the homestead he finds the child literally sitting on a fence, in between his father and the mysterious cowboy. Scenes of this nature are replicated in Drive where the Driver confronts the family in unclaimed spaces such as doorways, hallways, and crucially, elevators. The family in Drive, like in Shane, are being harassed by criminals and outlaws. Through his journey the Driver then becomes like Shane as he rises above his own needs to protect the sacred institution of the family. He uses his car, like cowboys use their horses to enable him to defeat the evil characters who seek the destruction of the family. The western cowboy is often a kind of invincible human, the superhero who puts the family before his own needs. In both Shane and Drive he is ultimately too noble and innocent for the modern world and rides off in an unknown condition in between simultaneous states of life and death. A contentious object in Shane is the gun, it separates what the cowboy is from what the father is and this object fascinates the child and draws him to Shane’s image. While Shane is a paragon of justice, he is still a death dealer and a gunslinger. In Drive, part of the Driver’s code is to never carry a gun. However, he is still a character who commits brutal acts of violence throughout his journey. Refn then takes the cowboy and strips him of the prop of the gun, a classic trope of the western genre. In a brilliantly shot scene in the backstage of a strip club the Driver is seen about to hammer a bullet into the head of one of the criminals who has been chasing the family. The

bullet was given to the child of the family as a sign of imminent death. The Driver takes the bullet from the child and resolves the problem by not using guns. Conversely, in Shane, the cowboy embraces the gun and teaches the young child how to shoot. The Driver’s no gun policy then shifts the type of hero that he will eventually become. The fetishisation of the gun in the Western genre was replicated in vigilante-justice films such as Taxi Driver ( 1976) and Dirty Harry (1971) but the all conquering gun has recently been taken from the hands of the modern hero. Drive bears many similarities to the Eastwood film Gran Torino (2008) where the old cowboy then abandons the gun for the good of the family. However, it is still a very masculine view of the hero without a gun. In removing the gun from the hands of the Driver, Refn instead gives him other props to show his hero/superhero nature. The leather gloves heard wrenching in the opening scene are both an enabler for his driving skill and signify key moments of violence and tension. However, these gloves are a more sexual and bondaged view of the nature that violence takes in the film. In these scenes Refn over-sexualises the violence and deconstructs the masculinity of the cowboy. The Driver effectively defeats the gun-toting gangsters by adopting fashion props, such as the gloves or the iconic scorpion jacket. The superhero image is reversed with the jacket as the Driver wears his superhero symbol on his back rather than on his chest, such as Superman. Refn’s treatment of the superhero/cowboy then forces us to consider our love for the hero with a code. With the Driver, this love becomes a fetish and reveals the viewer’s darker fascination for the hero bondaged by a specific code of morality.

Refn’s next film will be Only God Forgives (2013). The initial shot from the film that we have draws in the voyeuristic viewer who will want to see what has caused this damage to one of Hollywood’s most famous faces. Just as he has removed the cowboy’s gun, he will next remove another trope of the traditional hero – the good looks of the actor; a feature which was celebrated via Ryan Gosling in the film Crazy, Stupid, Love. (2011).

Works Cited

Bronson. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. Perf. Tom Hardy, Kelly Adams, and Luing Andrews. Vertigo Films, 2008. Web.

Drive. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. Perf. Ryan Gosling, Carey Mulligan, and Bryan Cranston. Icon Film Distribution, 2011. Web.

McMahon, Jennifer. The Philosophy of the Western. Lexington: University of Kentucky, 2010. Print.

Valhalla Rising. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. Perf. Mads Mikkelson, Maarten Stevenson, and Alexander Morton, 2009. Web.